Metamorphizing Our Symphony 3: Towards an All-Music City

Original Kitchener, Grand River Country, Ontario, Canada, May 20 2024

One of the obstacles to making sure that the KW Symphony gets a chance to begin another chapter is the commonplace impression that this is a project dedicated to an outdated musical form dominated by the works of a limited range of creators, mostly men from Old World aristocratic regimes who died long ago.

I’m in the habit of talking about the Symphony Orchestra, with its purpose-built instrument, the Raffi Armenian Concert Hall, and the parent organization, known today as the Grand Philharmonic Choir, as a “legacy.” I realize, however, that this may actually be detrimental to the cause.

It is certainly true that we’re talking about a story that goes back to 1945, when the orchestra project was set in motion, or to 1922, when the choir began operations, or even further back, to 1883, when a group of Waterloo County residents came together to form the Berlin Philharmonic and Orchestral Society.

It is important, though, to dispel the impression that we are engaged in a retrogressive “Make Our Orchestra Great Again” campaign, or that we’re isolating and elevating classical music as the crowning achievement of human creativity, and therefore the top priority for any and all kinds of support.

In terms of Saving Our Symphony at the present moment, the dates that really matter are 1971, when Raffi Armenian arrived to begin transforming an outstanding community orchestra into a world class professional organization, and 1980, when the doors to that marvellous concert hall opened. It is important to keep in mind that these are relatively recent developments -- roughly coterminous with the beginning of our peculiar two-tier municipal structure, the amalgamated city of Cambridge, the founding of the Waterloo Regional Arts Council, and the area’s first cultural strategic plan in Waterloo.

“Legacy” as an adjective has developed negative associations, as in “legacy media,” for instance. Museums, galleries, orchestras, concert halls and time-honoured festivals are sometimes viewed the same way: as the mainstream, the establishment, the “elite arts,” and as such, a burden on scarce resources.

Innovation is commonly equated with disruption. A preference for disturbance has been around for a long time. It may, in fact, be a definitive characteristic of modernity itself. Seeing the past as an obstacle has been the prevailing view for going on 250 years now. It is so prevalent, and so deeply ingrained in the modern mindset, that suggesting, at this late juncture, that maybe it's time to move beyond the idea of progress as destruction to clear the way for beginning anew could be seen as a kind of counter-disruption.

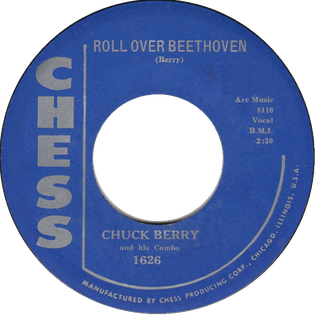

In relation to the current situation of the KW Symphony, that great anthem of disruption from the high modern era keeps coming to mind: “Roll over Beethoven and tell Tchaikovsky the news.” The message is clear, and appropriate for the time: The war was over, money was circulating, the austerities of the depression were not returning, and cities and towns were teeming with children and youth: It was time for the old guard to get out of the way, and make room for a new generation that, as Chuck Berry predicted, would soon be “rockin’ in two by two” all over the world.

Roll Over Beethoven hit the charts 68 years ago this month, which means that three or more generations have emerged since then. Our present is more distant from the birth of classic rock than Chuck Berry’s declaration of joyful intent was from the moment when Tchaikovsky gave his Nutcracker ballet suite to the world (which was a year before he passed away, in 1893).

Going on 70 years ago everyone imagined Beethoven and Tchaikovsky rolling in their graves when they heard the news that Berry was announcing, but it is more likely that, when they got a sense of those new sounds girls and boys were rocking, rolling and moving over to, the great masters jumped for joy along with almost everyone else, here on earth and in the afterlife.

In retrospect, what appeared to be the overthrow of an old order was actually yet another layer of cultural inheritance taking shape to further enrich the human race for all time to come. The era of classic rhythm & blues, rock’n’roll and all its variations was only just beginning at the time; there were many more layers of heritage still to come.

As we reach the end of the first quarter of the 21st century, it is becoming apparent that it has been a while since we've seen anything really new emerge on the popular music front. What comes next remains to be seen. It almost certainly will not be from London, New York or L.A.. Meanwhile, all those layers of legacy we all share are continuously being mixed and remixed in an infinite variety of ways. It’s all classical; it’s all modern, and it all rolls along.

The KW Symphony story runs parallel to these and other developments over time: The founding of the Berlin Philharmonic and Orchestral Society coincided with the emergence of cities as we know them, with newspapers, department stores, streetcars, parks, concert halls, museums and galleries. The Philharmonic Choir was formed as radio broadcasting and audio recording became part of daily life. The Kitchener Waterloo Symphony arrived just before TV and rock’n’roll were coming into their own. Raffi Armenian’s contribution to the legacy are of the same vintage as the emergence of punk, disco, hip hop and MTV.

The “Roll Over Beethoven” refrain also went through my mind at the Music City panel discussion that took place at the SDG Idea Factory shortly after the news broke about the KW Symphony board abandoning ship. Waterloo arts and culture stalwart Betty A. Keller began her remarks as one of the panelists with a reference to the 52 musicians who had just lost their jobs, but the subject didn't come up again in any of the presentations or in the lively discussion that followed.

There was, however, one indirect reference that did strike me as an expression of old-fashioned “Roll Over Beethoven” defiance. The Music City panel was centred around the presence of music and cultural policy consultant Shain Shapiro, who was on tour promoting his first book, This Must Be the Place: How Music Can Make Your City Better. The emphasis was on what Shapiro referred to as the music industry, or the “night time economy.” To foster a vibrant music ecosystem, consideration of the distinct needs of the industry and appreciation of the benefits it can bring must become an integral part of all aspects of city planning.

The “Roll Over Beethoven” moment came when someone quoted Shapiro talking about municipal leaders being stuck in their old ways investing in “orchestras and festivals” when they should be thinking of night clubs, liquor laws, noise restrictions, zoning and intellectual property rights. The antagonism implied here seems unnecessary, and misleading. Orchestras, concert halls, museums, galleries and libraries belong in the same category as parks, gardens, landmarks and monuments, which have only a tenuous connection with the commercial music business.

The popular music industry may still seem youthful and modern. The main concern here, though, appears to be stabilizing an industry that has been facing challenges that are not all that different to the trends that have devastated legacy newspapers all over the world. When the Mayor of London (Boris Johnson before he became notorious) hired Shapiro as a consultant, it was to save his city’s vibrant music scene. We’re not talking about disruption, but adaptation, restoration and conservation.

The Music City event, like the organization behind it, the Midtown Radio project, was mainly about the regional independent music scene. But it wasn’t all indie music. I recognized people from local jazz, blues and hip hop circles. What struck me, though, was who was missing from the assembly: To begin with, I didn’t see anyone from the spectrum of musical forms covered by The Music Times: “chamber, experimental, new, orchestral, vocal, wind ensemble.”

The Waterloo-Wellington classical music scene extends into sacred or church music, as well as the rich range of community choirs, bands, orchestras, musical theatre organizations and venerable citizens bands. Taken altogether, these elements constitute a formidable presence in our communities, and could serve as firm ground for any claim we might make for “music city” status.

Despite what’s going on with the KW Symphony, this is a field in which we have always excelled. I can’t think of anything else that distinguishes us in the same way this deeply rooted musical legacy does. Since it is attributable, in large measure, to the continental German strain in the “Waterloo Way,” it is a far more authentic and meaningful expression of this aspect of the culture of our region than something like Oktoberfest can ever be.

The kind of music that Neruda Arts presents through Kultrun and All That Wordly Jazz -- global indigenous, multicultural, and what they call world music -- was also noticeably absent from the Music City assembly. This extends into the range of global traditional and folk music featured in the now gone but not forgotten Mill Race Festival of Traditional Music that once distinguished Galt so effectively.

The polka and waltz flavours of Oktoberfest also belong in this category, as do the traditions celebrated by Grand River Flamenco Festival and the ceili phenomenon set in motion by the Irish Real Life movement.

What we have here, at this point in time, is not a classical and a contemporary scene running side by side, or old ways mingling with the new, but a cumulative harvest of cultural offerings that belong to all of us, a legacy that is very much alive, understood, appreciated and constantly being revised and adapted.

The KW Symphony isn’t the crowning glory of all this creation, but it can, because its size, quality, longevity and association with some of the region’s distinguishing elements, be considered as the cornerstone of arts, culture and heritage in our community. It doesn’t represent a past that weighs us down, stifles innovation or requires disproportionate levels of support, but the very opposite: The cornerstone supports the entire edifice.

Or maybe its the other way around. Perhaps we’re not talking about maintaining what others have built, but about the construction of something comparable to an arch or dome. An archway has two points of origin; maybe Homer Watson and his studio are the other foundational element, along with the Philharmonic and Orchestral Society. The task ahead of us is completing the work of seven generations or more with a keystone that will lock everything firmly into place.

This is related to the point I’ve been trying to make since the days when it was my responsibility to keep the Waterloo Regional Arts Council operational: How the arts are not a special interest or sector, but an all-points connector.

That’s why I’d like to see an All-Music City panel discussion, if possible at the same “Idea Factory” that hosted the first one, dedicated to bringing all these elements together.

Music can, in turn, as Shain Shapiro pointed out, serve as a point of connection between all the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals set for 2030, especially #17: Partnerships for the Goals. What we’re moving towards is a convergence of all the challenges and all the opportunities the can lead residents towards caring enough to become actively engaged with the city or town where they live, work and learn.

Arts, culture and heritage are ordinary, and universal. So let’s start thinking and talking about music and dance as what we do as human beings. The joy is in the making, which involves work, play and learning, but it is also in the receiving, which can involve active participation, but also abandonment: freeing yourself from everything you know, including all fears, cares and obligations, and drifting into the realm of wonder, where thoughts, words and even sight no longer matter.

This is not diversion or entertainment, nor is it relief or escape from the mundane. Music and dance in all forms, past, present and future, are how we get real.

Well said Martin. Thanks for sharing.