Town & Country Prospects Part 1: The A-word

Original Kitchener, February 13, 2023

The A-word is rearing its ugly head again. There is absolutely nothing to be gained by promoting or opposing “amalgamation” in the crude, 20th-century sense of the term applied to the civic realm. The last thing we need right now is an emotion-driven “debate” that reduces an infinitely complex range of issues, considerations and possibilities down to a flat “yes or no” proposition.

“It’s working in Hamilton,” I’m hearing people say. Kingston and Ottawa haven’t fared so badly either. But those were annexations, not amalgamations. These are all instances of dominant population centres annexing contiguous suburban areas, including adjacent farmlands and some historic towns and villages that had the misfortune to be overrun by sprawl.

In Toronto 25 years ago, we saw the original city area forced to take over older suburbs, while leaving a range of newer, more prosperous suburban configurations independent.

In places like Prince Edward County and Chatham-Kent, it was dissolving town and city distinctions back into the original county matrix. The advent of Greater Sudbury is comparable, but it covered a more extensive territory in a decidedly different part of Ontario.

In Brant and Quinte West, it was smaller communities banding together to block being absorbed by a dominant regional power centre.

Amalgamation -- the combination of two or more corporations into a new entity -- is actually a rare occurrence among bodies politic. Annexations, agglomerations and dissolutions are more commonplace.

No Place Like Home

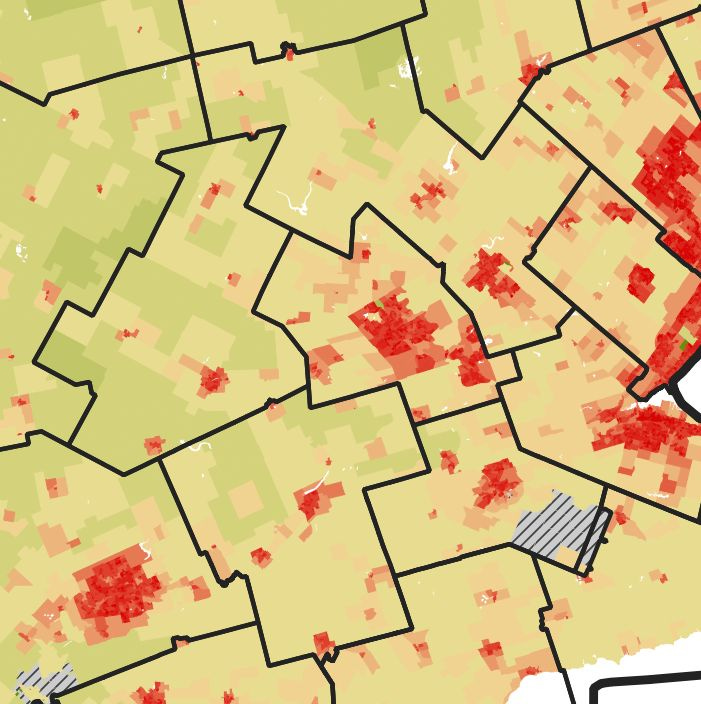

The situation here is unique: three distinct cities, a matchless constellation of historic towns and villages, and some of the most productive farmland in Canada, all coexisting with an overwhelming majority of residents who live in high modern suburban neighbourhoods. There is no readily comparable urban configuration, certainly not in Ontario.

Another factor that defines and distinguishes who we are is the Grand River watershed, including the fact that modern settlement here began with the Haldimand Tract, land granted to the people known as the Six Nations of Grand River Country.

The dangers, and the advantages, of existing so near the Great Metropole, her power and influence amplified by the province’s near total control over the municipal order also have to be taken into account. So does the power and influence of two major regional centres that are close by: London and Hamilton. As a result, relations with small to mid-sized cities and towns nearby -- Guelph, Fergus, Elora, Brantford, Paris, Woodstock, Stratford -- are more important, and more delicate here than in other places.

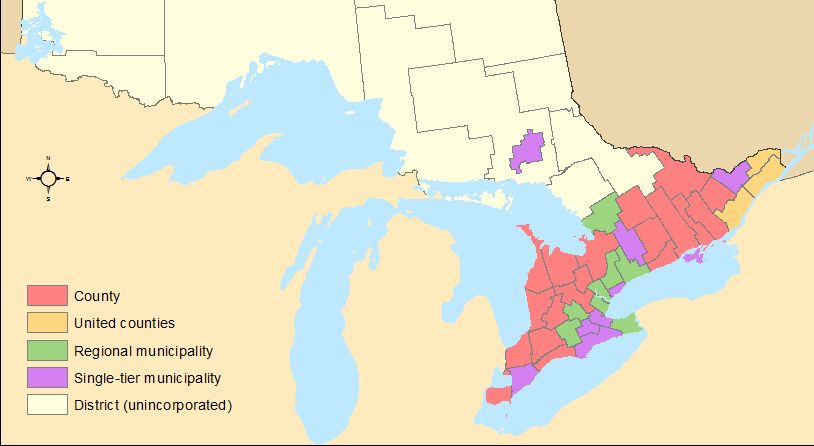

The peculiar two-tier municipal order we’ve been saddled with for half a century also sets us apart from the norm.

As a result, standard, cookie-cutter solutions don’t work here. It doesn’t have to be made-in-Waterloo solutions exclusively, but they do have to be bespoke measures, carefully fitted for the communities of the Greater Waterloo area as they have grown to become today.

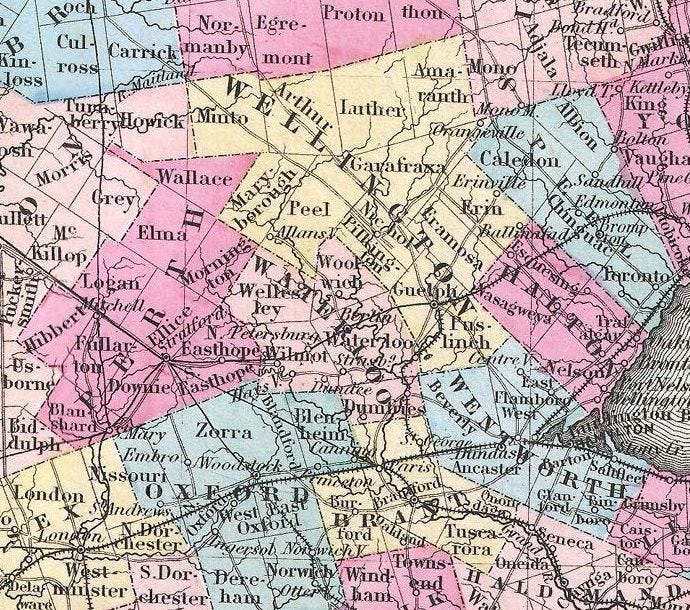

At the same time, there are aspects of all the annexation, agglomeration and dissolution scenarios cited above that apply to our situation: In relation to the GTA, we’re like Quinte West vis a vis Belleville, or Brant in relation to Brantford. But then again, so is Cambridge in relation to the dominant KW establishment. Before 1973, Waterloo was one of the strongest “county” brands in the country, so a Prince Edward County approach is worth examining, as long as it doesn’t distract us from the reality that this is a major Canadian urban configuration.

Happenings Fifty Years Time Ago

The dissolution of the Galt, Preston and Hespeler and the establishment of Cambridge fifty years ago can be seen as a rare example of an actual amalgamation. Galt is larger and has remained dominant, but extending the city’s limits to encompass two substantial towns that were, with Kitchener and Waterloo, originally part of Waterloo the township distinguishes what happened here from a normal annexation, like Dundas being taken over by Hamilton.

The question we need to ask is: Has this example of an actual amalgamation been an unmitigated success? If so, dissolving Cambridge, Waterloo, Kitchener and the townships back into the Waterloo County matrix from which they originally emerged would be a logical next step.

The dissolution of the County of Waterloo fifty years ago and the imposition of our current two-tier order was something else again. This was a novel experiment. One can imagine regional government in Niagara, Oxford, Waterloo, Muskoka and some outlying areas of the GTA as pilot projects. If that’s the case, the powers that be must have considered them failures because they never tried to impose the model again in any other Ontario community.

The fact is, those clumsy attempts at municipal reform of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s created more problems than they solved, especially in difficult to measure matters such as integrity, identity and civic engagement. That doesn’t mean that the existence of the amalgamated City of Cambridge and the Regional Municipality of Waterloo aren’t something to commemorate at the fifty-year mark. But if there is cause for celebration and self-congratulation, it would be for how well we’ve managed our cities and towns despite what provincial bureaucrats did to us back then.

Our saving grace has been that the structures that were put in place back then left sufficient room for adaptation. We’ve come a long way, making adjustments here and there. This is a good time to consider what was gained and what was lost in 1973, and to evaluate the improvements we’ve made since then: what has remained stable; what has changed over the years; what works; what hinders further progress, and, most important, how to best adapt to 21st century realities.

The lesson to be drawn here, I think, is that all political arrangements are best treated as provisional. We can all agree that there is room for improvement, not just on the municipal front but in many aspects of democracy as it is practiced in Canada. The two-tier arrangement here in Waterloo Country may be awkward, but the two-tier federal-provincial relationship, which has been a constant mess from the outset, is far worse. It has saddled us with a huge backlog of matters left unresolved, and left things at an impasse on multiple fronts.

That needn’t lead us to the conclusion that Canada is broken, or that Waterloo Region is dysfunctional. On the contrary: no other nation state, and no other city-region is better equipped to deal with the challenges and seize the opportunities immediately before us. Whatever we do here in terms of political reform would be building on strengths developed through the experience of having to deal with the inadequacies of the system for half a century. I think we’re ready, regionally, provincially and federally, to raise expectations, and take things to a new level.

Cultivating a Sense of Possibility

Constant improvement on all fronts is better than a total makeover every generation or two. A revolutionary turn would be un-Canadian. Our very existence as a sovereign nation state is based on a rejection of tearing down established order, erasing the past and beginning everything anew. But that doesn’t preclude a courageous leap forward towards an integrated and harmonious political order in and among the communities of Greater Waterloo, and while we’re at it, in and among the various Canadas.

So let’s banish the A-word from our speech and our thoughts, and talk about alignment, balance and harmony instead.

The question to ask is the one Professor Rick Haldenby raised at a talk a couple of years ago: "What kind of city are we building?" It was addressed to people who care about Kitchener, but it also applies to people who care about Galt or Waterloo (or Guelph, Brantford, Woodstock, Stratford … ). For people who care about Preston, Hespeler, New Hamburg, Ayr or Elmira, it would be “what kind of town do we want to be?”

The best place to begin is a purposeful vision for the immediate future that is courageous, aspirational and achievable, and a set of values and principles to match. That means leaving behind those tiresome voices who talk about municipal reform as an efficiency measure, or primarily for “branding” and other forms of hackneyed commercial boosterism, or just so that there will be “fewer politicians.” What we want to cultivate is “a sense of possibility”*-- a collective capacity for imagining, the courage to dream up and attempt things, and the confidence we’ll need to be able to seize an opportunity when it presents itself.

The next step could be a comprehensive 50-year road map, grounded in actualities and informed by reflection on how things have unfolded over time with emphasis on the last 50 years. Wise planning is provisional: it avoids, whenever possible, prioritization in order to make the most of variation in what good-hearted people care about and are willing to work towards. We’d also be wise to leave ample room for adaptation as new arrivants and new generations become part of the body politic.

Once we get a clear sense of what we want to accomplish, we can make whatever adjustments to the current order that might help us achieve our objectives. In some areas of concern this might mean a single harmonized planning order, but it is just as likely that devolution and decentralization will prove to be the best way forward. Ideally, we will learn how to reconcile what only appear to be polar opposites.