Town & Country Prospects Part 5: Fragments and Figments

Original Kitchener, Ontario, Canada April 21 2023

The train of thought I’m sharing in this Evening Muse post began with the headline over a recent Luisa D’Amato Opinion piece in the Waterloo Region Record, particularly the idea of Cambridge -- our Cambridge -- as “a fragmented city.”

It is questionable whether Cambridge, Ontario, is, or has ever been, a city at all -- at least not in the sense of the city as an actual, living organism, with a discernible starting point and continuous development, traceable through rings of growth over time, much like the cross section of the trunk of a tree can tell the story of its life.

What we know as Cambridge began, not with a founding settlement, but as a figment hatched in the imagination of some ministerial bureaucrat in Toronto. The figment became a plan that was implemented 50 years ago, in typical 20th-century style, with an arrogant assuredness that these experts knew what was best for the rubes actually living here.

The Cambridge idea was to install a simplified new order on a diverse set of organic communities that had been flourishing over many generations as Waterloo County settlements, mostly on sections of the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations of the Grand River. Fifty years later, those communities – a substantial Canadian city, two thriving towns and a very special historic village – all remain extant, functioning as the “fragments” D’Amato talks about in her piece.

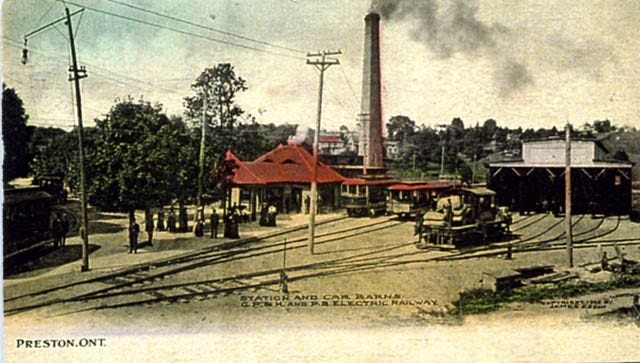

To my mind, the stubborn persistence of a differentiated sense of place in these communities is a blessing, not a hindrance. They all continue to maintain a day to day existence, each in their own way, so that the spirit of the place remains readily recognizable as true to the original form. There may be signs of wear and tear here and there, but the fact that, half a century after being shoehorned into an artificial managerial configuration, Hespeler, Preston, Blair and Galt remain more or less intact is something to celebrate.

There have been some bad breaks, to be sure. The article mentions the Cambridge sports complex debacle, which certainly stands out as an embarrassment for all involved. The “ferocious” and “nasty” tone of the outcry that ended up derailing the project is usually attributed to the rise of social media. Let’s keep in mind, though, that this new form and style of public discourse emerged in what had been reduced to a near vacuum in terms of a local media presence. Cambridge lost its daily newspaper just when it needed one most: to inform the public and serve as a forum for deliberation on how to make the best of those peculiar political arrangements they’d been saddled with.

The damage, both physical and in the nebulous area of general morale, has been severe in some places (I’m thinking of the recent loss of the last remains of the Preston Springs legacy in particular). But this may be because there is so much more to lose in this part of the region, and not because of amalgamation per se. When it comes to loss of identity, authenticity and cultural inheritance, there are other Waterloo County/Region communities that have fared much worse.

My sense is that the dismantling of Preston and Hespeler as corporate entities has hindered Galt from becoming all it could be more than it has hurt the smaller fragments. In much the same way, Kitchener has been held back by the dominance of what could be called the “KW mentality” more than Waterloo has. But there has also been progress. For both of the new municipal structures that were set up here 50 years ago -- Waterloo Region and Cambridge -- the bad breaks have been far outweighed by a steady flow of good fortune, especially in the area of political leadership. An amalgamated Cambridge inserted into a cumbersome two-tier regional configuration was one bad idea compounded by another, but our communities certainly made the best of what we were dealt.

The Cambridge sports centre story led Luisa D’Amato to the conclusion that with “different communities all vying for their fair share of resources, it’s very difficult to build anything for the whole city. Or find a unified sense of purpose.” Let’s not forget, though, that while the amalgamated municipality may not have been able to create a state of the art athletic facility in partnership with Conestoga College, they have been able to build outstanding civic assets, perhaps better than in any part of the region: Cambridge Centre for the Arts, a splendid new City Hall, a public square, the Waterloo Architecture campus, the Cambridge Sculpture Garden, the Old Post Office digital library facility, Hamilton Family Theatre, Fashion History Museum and the Hespeler branch of the the city-region’s library immediately come to mind.

“Different communities all vying for their fair share of resources” is a phrase that could readily be applied, not just to all of Waterloo the former County, but to Canada as a whole. But is this really how it works? Do the fragments actually resemble a nestful of helpless creatures, beaks agape, crying out for their share of what mama and papa dole out? It may be that at certain stages of development we are not capable of either fending for ourselves or taking care of one another, but with a normal level of maturity, both as individuals and as members of a community in any form, we can only achieve what we set out to achieve, and only become what we decide to become.

Whether on a national, provincial, municipal or even a familial plane, a “unified sense of purpose” would be stultifying. A body politic on any scale is an infinitely complex whole that serves many purposes, personal and associated. It is better to seek congruence among multiple purposes than force conformity through prioritization and concentration. Instead of trying to speak with one voice or conform to a single will, let’s nurture a guarded trust in the possibility of harmony in multiplicity.

While varied interests can appear to be at cross purposes, I honestly believe that, fundamentally, they need never be. Just as a diversity of voices is a prerequisite for harmony in music, so it can be in the political or civic realm. Removing or ignoring differences creates a dull monotony, which also happens to be a common result of the iron rule of a tyrant, a data-obsessed determinist or a single-minded ideologue. A logical first step towards achieving a civic order that is fair, wise and effective is choosing to pursue harmony in diversity.

Cambridge is not, has never been, and will never be “a city.” It is an administrative unit set up to manage a constellation of historic communities surrounded by vast expanses of modern suburban development. In the same way, the Region of Waterloo is not, has never been, and will never be “a city.” Functionally, Cambridge is a regional municipality subsumed under another regional authority that is broader, and therefore generally assumed to be higher. According to the prevalent mentality of late ‘60s and early ‘70s, this may have seemed a sensible arrangement. Fifty years later, it looks antiquated, awkward, and in some respects, downright absurd.

Could a fresh figment hatched in another bureaucrat’s imagination help realign all the fragments in a fair, sensible and enabling way? I don’t think so. And if we did happen to get our act together, it wouldn’t take us very far. It is becoming increasingly clear that any kind of reordering within the municipal sphere alone would be inconsequential. As Luisa D’Amato asked in an earlier opinion piece, in this case about public opposition to yet another gravel pit in Wilmot Township: “What’s the point?”

What’s the point … when with one ill-considered move, Premier Doug Ford can sweep all your work off the table? … If municipal councils have so little power over the things that are so important to us, then why even vote in municipal elections? Why have municipal councillors?

Really, what’s the point?

What does it matter if we have one mayor or three mayors; one, two or three public squares; seven, eight or ten ward councillors, when, in a process that could be described as re-colonization, the powers that created our counties, townships, towns and cities, re-absorbs them all back into the single imperial matrix from which they came?

Wilmot decided not to resist the gravel interests; Woolwich isn’t going to stand up for Maryhill. There may be a chance that the North Dumfries moratorium on aggregate extraction will hold because the situation there is so extreme. Baden, New Hamburg, Ayr, Maryhill – more fragments. If we give questions like the ones D’Amato raises in both these pieces the attention they deserve, there’s a chance that the fragments will start falling into place. There is a lot of common ground, starting with the very ground we live on, on an equal plane, shoulder to shoulder, face to face.

The point, as I see it, is that by continuing to care about the various fragments, and by carrying on with thinking and talking about how they relate to one another, to the land and the waters, and to the challenges we all face, we may begin to realize that the 21st-century alternative to a 20th-century style of monolithic unity is an integrated, harmonious whole in which the constituent elements remain distinct and true to form.

When we get that far, we’ll also realize that an integrated Waterloo, a well-tuned Waterloo-Wellington, or even a harmonious assembly of Grand (or Willow) River nations and settlements, would still be just a fragment. To set things on the right course, and to ensure that there continue to be sound reasons to come out to vote in a municipal election, and to stand up as citizens engaged in the civic life of Wilmot, Woolwich, Kitchener, Waterloo, Cambridge or any fragment thereof, we’re going to need to become a harmonious Ontario and an integrated Canada.

I’m not talking about a feel good, “buy the world a coke,” sing a joyful tune kind of harmony. But it is all about real things: constellations of cities, towns and villages; meadows, fields and woodlots; lakes, rivers, creeks and wetlands; churches, schools, libraries, museums, galleries; landmarks, parks, playing fields, swimming pools and heritage districts. There is no fragment, no single element within all that reality that is fundamentally, irreconcilably at odds with any other.

The survival of the fragments is living proof of the strength of our communities. We must stand firm, not yield an inch, but also always remain confident of that strength. When Doug Ford sends his appointed saviour to tell us how to run things it is unlikely that anything they end up imposing this time around will cause permanent damage. Whatever happens, we’ll make the best of it. If there are setbacks, I’m sure we won’t have to wait 50 years to recover. Things will get back on track just as soon as the road to a sustainable and prosperous future is clear again.

P.S. I haven’t touched on the bad break that is the main topic of D’Amato’s opinion piece: the news that the estimated price tag for completing the region’s rapid transit system by extending it into Cambridge has ballooned from $1 billion to $4.5 billion. Does this mean that, as Luisa D’Amato and Doug Craig seem to have concluded, that “the project is effectively dead?”

We’ll ponder that question in another Evening Muse.