Town & Country Prospects Part 2: Bigger Isn't Always Better

Original Kitchener, February 21, 2023

This is the second installment of a projected sequence of musings about the promise and the perils of imminent municipal restructuring in and around what I like to call “Waterloo Country:” the communities of the region in whole and in part, along with the ground they stand on, as opposed to just the Regional Municipality. I’m following a train of thought introduced in Town & Country Part 1: The A-word, which suggested:

That amalgamation -- the combination of two or more corporations into a new entity -- is actually a rare occurrence among bodies politic. Annexations, agglomerations and dissolutions are more commonplace. So let’s refrain from applying the term to our situation, and talk about alignment, balance and harmony instead.

That the situation here is unique. There is no readily comparable urban configuration, certainly not in Ontario. There are, however, certain aspects of all the various municipal reform scenarios we’ve seen unfold over the last 30 years that do apply to current circumstances here in Waterloo Country, including Toronto, Hamilton, Kingston, Ottawa, Chatham-Kent, Quinte West and Prince Edward County.

That all political arrangements are best considered provisional. Constant improvement is better than a total makeover every now and then. A revolutionary turn would be un-Canadian, but that doesn’t preclude a courageous leap forward towards an integrated and harmonious political order in and among the communities of Greater Waterloo.

That the best way to begin a significant leap forward would be to articulate a purposeful vision. Once there is a clear sense of what we want to accomplish, we can make whatever adjustments to the current order that might help us achieve our objectives. In some areas of concern this might mean a single harmonized planning order, but it is just as likely that differentiation, devolution and decentralization will prove to be the best way to proceed. Ideally, we will learn how to reconcile what only appear to be polar opposites.

Corporate Aggrandizement

Part of the reason why simple amalgamation doesn’t suit a body politic of any shape or on any scale is because it is a model that emerged in the world of private business corporations. The golden age of agglomerated enterprise in our part of the world lasted from what they call the Gilded Age in the U.S. to the Great Depression. Think of all the familiar brands that have signifiers such as United, Union, Consolidated, Federal, Federated, General, Continental, Atlantic, Pacific, Standard, U.S., American, Canada, Canadian, Dominion, British American, British, Royal, Imperial or International as part of their title.

The drive towards corporate consolidation is still with us, but the preferred terminology today is “merger,” “acquisition” or, simply, “growth.” This tendency has generally been viewed with alarm. Starting with the “trust-busting” movement of the Progressive era, we expect our governments to take measures to ensure competition remains open to some degree. Aggrandizement, however, is a natural process: A competitive corporate endeavour is, by definition, a conspiracy against a free and open market, dedicated to acquiring, eliminating or excluding competing interests.

Consolidation can stifle innovation and experimentation, and often leads to stagnation. When the North American auto industry was finally winnowed down just the “Big Three,” it lost its dynamism with dramatic speed. Leadership in the field passed over to Asia and Europe, where it has remained ever since. Globalization allowed a more open and competitive environment, which benefited all parties, including what remains of the historic car and truck brands of North America.

In a similar way, the emergence of independent craft beer and wine operations, in this case on the local and regional front rather than in a global context, is enriching and enlivening tired industries dominated by a few remaining legacy operations.

The most glaring example of near monopoly leading to stagnation, and finally, a dead end is Greyhound in the field of inter-urban motor coach transportation. Just when the company’s continent-wide dominance reached a peak, its leadership decided to simply walk away from the industry altogether. A company that had secured 90% of inter-city transportation by bus in Germany was able to pick up what was salvageable out of the wreckage of a once proud brand.

What’s interesting here is that neither foreign competition nor new technologies were a major factor in this example of a corporation dominant in its field summarily abandoning its purpose and mission. The question arises: to what extent has self-immolation of mega-corporations in other sectors followed the same pattern? Local and regional print journalism and broadcasting, for instance. What began as a system of networks and chains gradually devolved into a few centralized, top-down, monolithic mega-corporations that soon began collapsing under their own weight. The near disappearance of North American manufacturing in general could be part of the same phenomenon.

The point is: Bigger isn’t always better. Smaller is not always always better either; separation and secession are rarely a solution. We are, however, always better together, in free association, open communication and at peace with one another -- always, and in every way.

Freedom and Association

A body politic is a kind of corporation, especially if it’s a city or a town. Like other collective endeavours, cities and towns were either formed voluntarily and intentionally, usually with a charter from one authority or another to legitimize their existence, or acquired at some point by conquest, claim or purchase by an aggrandizing force, imperial, colonial, national or corporate.

It is when freedom, self-determination and democracy become part of the picture, as is the case when anything is done voluntarily and deliberately in any body politic, that things get complicated. Amalgamation is something done to, not by a corporate body. When there’s a measure of freedom allowed (which I’m not sure there is when municipalities are considered “creatures” of provincial authority), the process becomes joining, associating or merging.

Ontario’s cities all began with a form of separation, usually from the province-colony’s original county matrix. The process is analogous to the life cycle: a crossroads settlement or village is like an embryo; becoming a town is being born. City status is reaching adulthood. The difference is that a corporate existence, properly maintained, can go on forever, while a creature made of flesh and blood is mortal.

Because a city is an integral unit, it cannot secede from itself. But it can join, associate, merge, acquire and absorb. Among and within political corporate entities that have achieved or been allowed some measure of self-determination, the fundamental choice is between status quo, separation and union. The liberation of the Netherlands and the Swiss cantons, the Declaration of Independence, Brexit, the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and the establishment of home rule in former European colonies are all examples of the separatist impulse.

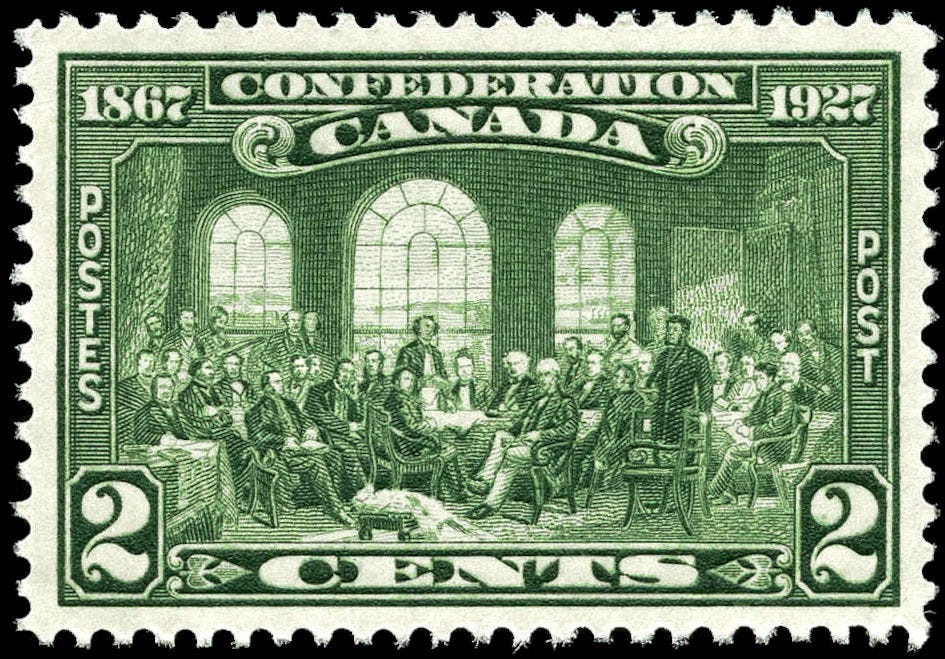

In many cases, newly separated nations become centralizing forces that achieve unity by absorbing constituent elements. But it is also possible to come together in order to preserve, rather than surrender an autonomous existence. Federations are a special kind of union. Outstanding examples include the Swiss Confederacy, the United Provinces of the Netherlands, the United States of America and the European Union. I’m not including Canada because our union did not follow a secession, which makes us a special case. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy is the most special of all.

Absorption into a union is not always forced. From what I gather, the amalgamation of Fort William and Port Arthur to become Thunder Bay in 1970 was mostly voluntary, made legal by the province following the results of a study undertaken at the request of local interests. The three United Counties formed in the oldest part of settler Ontario before Confederation are another interesting example: Prescott & Russell (1820); Leeds & Grenville (1850), and Stormont, Dundas & Glengarry (1850).

These were voluntary unions, like a love marriage, in contrast to Cambridge, which was more like an arranged or shotgun wedding. They are also all examples of full unions: two or three became one. In a federation, the association doesn’t erase or limit an autonomous existence: The new configuration doesn’t replace the parties joining forces, it can actually strengthen their autonomy in relation to the world at large.

I’ve suggested that a single harmonized planning order is not the antithesis of dissolution or decentralization, and that we should look for ways to reconcile what only appear to be polar opposites. That’s why I’m proposing that citizens who are looking for better local government in Greater Waterloo explore the possibilities of federation.

The federal path is not a compromise between union and self-determination, but a way to secure the advantages of both. An individual loses nothing by becoming part of a cooperative, a mutual or a partnership. In the same way, a city, town, village or neighbourhood needn’t lose anything valuable or important, certainly not their very existence, by voluntarily associating with others of a similar nature.

Done right, a federation renders each constituent element more free, more secure and more powerful than when it stood isolated and alone. A union that absorbs its constituent elements, or that betrays them by becoming an external, higher power -- an “upper” tier -- is a federation that has failed both the parts and the whole.

We will return to the theme of federation in a local and regional context in Town & Country Prospects Part 3: Better Together.